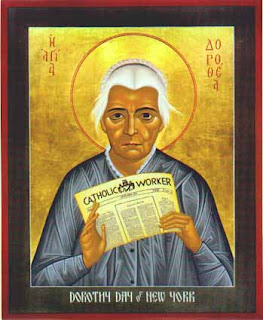

In advance of this month's

publication of

Dorothy Day's journals and next month's 75th anniversary of the

Catholic Worker Movement, the New York writer, activist and "model of holiness" -- whose

cause for canonization opened in 2000 -- is

the lead story in this week's

Tablet:

For much of her life, Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, was regarded as a prophetic if somewhat marginal figure in the American Catholic Church. Her combination of traditional piety and her radical stance on social and political issues posed a paradox for many people. She attended daily Mass, read the breviary, said the Rosary, and considered herself in all religious matters a "loyal daughter of the Church". At the same time she called herself an anarchist and backed up her pacifist convictions with tax resistance and repeated acts of civil disobedience....

The publication this month of Day's diaries, sealed for 25 years after her death in 1980, offers a new, intimate portrait of her activities and inner life. The Duty of Delight - a title drawn from a favourite line of Ruskin - covers her journey from the earliest days of the Catholic Worker Movement until the final weeks of her life. In a sense, the movement and Day's lifelong vocation were a response to a question she had posed herself as a child: "Where were the saints to try to change the social order, not just to minister to the slaves, but to do away with slavery?"

Many have long believed that Dorothy Day was the model for a new form of holiness. In 2000 the Vatican lent weight to this opinion when it formally accepted her cause for canonisation and bestowed the title "Servant of God". Her diaries certainly support this cause. Almost every page describes her intense spiritual focus and the discipline of prayer and worship that formed the structure of her daily life. "Without the Sacraments of the Church," she wrote, "I certainly do not think that I could go on." At the same time, the diaries chronicle her sometimes complicated relationship with church authorities, and her capacity to combine great love of the Church with suffering over its sins and failings. [Summed up by Day's famous line that "She's a whore, but she's my mother."]

In the annals of the saints, Day's diaries offer something unusual: an opportunity to follow, almost day by day, in the footsteps of a holy person. Through these writings we can trace the movements of her spirit and her quest for God. We can see her praying for wisdom and courage in meeting the challenges of her day. But we also join her as she watches television, devours mystery novels, goes to the movies, plays with her grandchildren and listens to opera.

While she was a witness or participant in many of the great social and ecclesial movements of her day, her diaries are a reminder that most of any life is occupied with ordinary activities and pursuits. Inspired by her favourite saint, Thérèse of Lisieux, Day was convinced that ordinary life was the true arena for holiness. Her spirituality was very much focused on the effort to practise forgiveness, charity and patience with those closest at hand.

Like most holy people, she often fell short of her ideals. We know this because she herself calls attention to her faults - her impatience, her capacity for anger and self-righteousness. "Thinking gloomily of the sins and shortcomings of others," she writes, "it suddenly came to me to remember my own offences, just as heinous as those of others. If I concern myself with my own sins and lament them, if I remember my own failures and lapses, I will not be resentful of others. This was most cheering and lifted the load of gloom from my mind. It makes one unhappy to judge people and happy to love them."...

In response to the insecurity, the sorrows, and drudgery of life among the "insulted and injured", she tried always to remember "the duty of delight": "I was thinking how, as one gets older, we are tempted to sadness, knowing life as it is here on earth, the suffering, the Cross. And how we must overcome it daily, growing in love, and the joy which goes with loving."

I knew Dorothy Day in the last five years of her life and I have spent many years since then studying her writings. The portrait that emerges in her diaries very much reflects the woman I knew: her interest in the concrete and particular over abstract theories, her love of literature, her eye for beauty, her capacity for joy, her spirit of adventure. And yet in transcribing and editing her diaries even familiar facts stood out in new ways.

I knew, for instance, that she was a woman of prayer. And yet it is striking to see that almost every entry begins with her rising at dawn to attend an early Mass. I knew of her devotion to her daughter and yet it was fascinating to follow her close involvement in Tamar's large family (she had nine children), with whom she moved in for months at a time, rejoicing in the pleasures of her grandchildren, at other times coping impatiently with their adolescent moods.

I knew that she had taken a six-month break from the Catholic Worker Movement during the Second World War. But I was surprised to learn that she seriously contemplated leaving the movement altogether. "What I want to do is get a job, in some hospital as ward-maid, get a room, preferably next door to a church; and there in the solitude of the city, living and working with the poor; to learn to pray, to work, to suffer, to be silent."

-30-

In advance of this month's publication of Dorothy Day's journals and next month's 75th anniversary of the Catholic Worker Movement, the New York writer, activist and "model of holiness" -- whose cause for canonization opened in 2000 -- is the lead story in this week's Tablet:

In advance of this month's publication of Dorothy Day's journals and next month's 75th anniversary of the Catholic Worker Movement, the New York writer, activist and "model of holiness" -- whose cause for canonization opened in 2000 -- is the lead story in this week's Tablet:

<< Home